|

I first realized that men and women read differently when I was 16, and I binged the Twilight books with love, only to emerge from them and find that… the world really disliked them. My first date with a guitarist was to the 2008 film, and his response out of the film was that “it was a girl’s film. He wasn’t supposed to like it.” We didn’t click well after that.

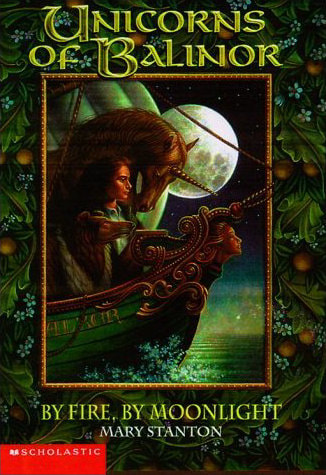

Not that the film for Twilight is very good (it’s not), but the dismissal of Twilight at large was a problem to me. It rang of the same dismissal I’d faced from bullies for liking dolls and unicorns (I’m seven here), the same dismissal I’d faced for enjoying Taylor Swift and Kesha (I’m fourteen here), and the dismissal I face later for enjoying shoujo manga and traditional YA, like Vampire Knight or Rainbow Rowell. “I just get tired of all the fairytales and boys,” I remember one friend saying. Keep in mind, this isn’t about quality: every kind of story has its share of garbage, and I’m not what one would consider traditionally feminine. But comic books and action novels typically have the emotional maturity of junk food, and I don’t hold them to a higher standard than that. Why then is girls’ fiction any different? Why is it cool to like comics and Star Wars, but a loss when women enjoy what may be more traditionally female? This issue is only a surface point to something deeper, after all. It’s the issue the demands female readers have ‘morally good’ role models in their fiction. It’s the issue that demands women change their pen names to something less… you know, particularly in science fiction and fantasy. It’s the issue that proudly compartmentalizes women’s fiction to YA, while snickering that YA is a childish genre. I’m not a “woman writer,” I like to claim. I’m a writer, and I also just so happen to be a woman: I don’t see these a mutually inclusive. Women’s stories are sometimes, as we’ve seen with YA and Twilight, labelled for simply being written by women, even when we have so much to offer for young readers. My endeavours into female-written fiction didn’t begin with Twilight, though I certainly give the series credit for creating the current environment in YA. But I started much younger, with the help of Mary Stanton and Cornelia Funke. I discovered Mary Stanton while browsing a newly-opened bookstore, back in the late 90’s; I am still too small to reach the top shelves on my own. I have a great collection of Barbies and stuffed animals for my ongoing political storylines, I have not quite outgrown my imaginary friends, but am old enough to keep them secret (spoiler alert: I never really do). My world is still small and colored with the veins of an odd feminism: Sailor Moon is everywhere, Britney Spears is the queen of pop. Stanton catches my eye because she writes the long-maligned horse genre (you know, for girls), and has added unicorns to the docket. I’m six, and unicorns are the best thing ever, so I grab the first book and try it. I devoured Unicorns of Balinor quickly, beautifully- saddened when I realized Stanton wouldn’t release anymore. To summarize eight books, a fantasy world princess, Ariana, recovers her memories after she is thrown into our world, then re-enters Balinor with her dog, a unicorn, and a girl named Lori. They go to stop an evil sorcerer and save Ari’s parents. It’s not… good fiction or very original (indeed, my well-worn copies are very young in tone), but they had good lessons in them, good adventures. Ariana might have been the first princess I ever encountered who was more interested in magic and her adventures than finding a prince to marry, or a pretty dress to wear. I touted them around my Girl Scout meetings and on car trips- #4 still have water damage from when I dropped in a puddle. I loved them, even though other girls around me disregarded them as “girly.” Unicorns were too girly… which confused me as a child. Even if they were, why was that so bad? Flash forward: I am twelve when I find Cornelia Funke, already knee-deep in comics, cool superhero characters, and Hilary Duff. My ears are pierced, makeup is a clumsy new tool that I never quite master. I have cut off all my hair after too many other girls started calling me “Hermione”, after my frizzy curls. I stop wearing my cute rainbow sweater and hip black boots to church or school, because the bullies get too relentless at clothes too. Being twelve sucked. I am given the translated Inkheart by a reading teacher whose face I remember more than her name. Excited that I liked books and have started writing (spoilers: that doesn’t go away either), she passes me a book about storytellers. I start the book at lunch that day: I complete it by the end of the week. I seek out the sequel, and the third novel, as they release over next few years. I bought all of Funke’s work, and still credit her as the biggest influence on the author I became. I loved that her adult characters were important and carried their own mature-for-the-genre plotlines; I loved that the children were just as troubled and awkward as I was. Though Inkheart and The Thief Lord are still my favorites, I am always drawn back to Inkdeath, the last book in her main trilogy. After reading it at 14, I left the book a bit confused. Meggie, the main character by most definitions, spends most of the adventure story improving herself and choosing between two boys: her original love interest, Farid, a thief pulled from Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves. And now, Doria, a young inventor pulled from a forgotten, yet-unfinished short story. A love triangle? This offended my sensibilities greatly, and what was worse- Meggie chose this new character over her love interest; she leaves Farid, feeling they were too distant to continue. Farid, though charming, is too dedicated to his craft and magic to truly love her. This left me so enraged, so annoyed as a teenager: “why would Funke reduce her to that? Farid was great!” I stayed annoyed about it… until I reread the book, and realized the kind of honest, adult truth the author had snuck into a Middle-Grade novel. Something brutal about first loves, and cute bad boys, and why we don’t settle. My jaw dropped; Funke wasn’t slacking, she was brilliant, and I’d fallen to the very girl hate that had long haunted me. Let’s return to Twilight, but really, to the disparagement of a genre full of serious love triangles, bad tropes, rescue romance, and fluff. Let’s discuss why we throw out Austen and Bronte as “boring” while highlighting Mary Shelley as “badass” because she started science fiction (a genre now, ironically, populated with mostly men.) Let’s discuss why women correct other women for taking on more traditional feminine interests, not just because it doesn’t appeal to them, but because society says it’s “bad.” Let’s really observe those things in ourselves. I loved Twilight when I was a teenager, and no, I probably wouldn’t read them again, but goodness, they were fun when I was 15. These days, I still find myself occasionally buying shoujo manga, I still love Rainbow Rowell, I still listen to Taylor Swift- all while enjoying gritty comics, dark fiction, and video games. I don’t really make a principled effort to dress more feminine or masculine. Because these things don’t matter, make me any less of a woman, nor any less of a feminist. In the world of feminist fiction, we should take pride that diverse topics allow women the right to choose their reading material, whether it be Twilight or Batman. That’s what makes them, well, people. I consider myself a person and a writer more than I consider myself a woman; society owes women the same.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About MeCaitlin Jones is an author, film editor, and lover of all things Victorian and fantastic. Please check in for information on her upcoming series. Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed