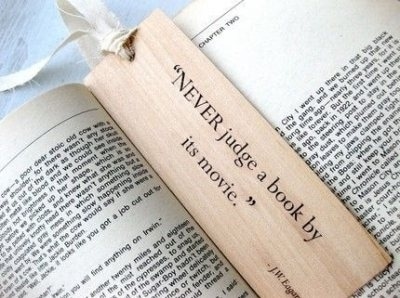

This weekend was an exciting one for bookish fanbases with the release of Netflix’s newest series, A Series of Unfortunate Events, a collection of adventures centered around the orphaned Baudelaire siblings and their notorious enemy, Count Olaf. The hype has been quite big for awhile: this is actually the second version of the popular middle grade series. Most readers would be happy enough to forget the first theatrical film by Nickelodeon and everything it brought with it though (I still personally cringe at the thought of the screeching, flailing take Jim Carrey had on the series’ main villain). The movie’s presence left permanent scars on the series. What is it about the movie-from-novel transition that is so harmful though? As we’ve seen in recent years, with films like Lemony Snicket or Eragon, or more recently- The Giver (see? I just cringed again), these movies can become deterrents from the original novel. If your first experience with a story is a Frankenstein’s Monster-like version of its content, you may never pick up the book or discover the actual story the author intended. Recently, t’s feeling like a book can’t even hit the shelf without first selling film rights; many publishers do reserve those rights ahead of time too, just in case, you know? It’s no surprise. As Harry Potter and Twilight climbed the ranks of popular fiction, their movies became larger-than-life franchises and gateways to the books for movie-goers. So everything gets a movie now, “and quickly! Before the audience loses interest and doesn’t care about this novel anymore. Who cares if some of the more literary themes in this book don’t make sense in a film?” And here lies the larger problem: books aren’t movies, and movies aren’t books. The strongest film adaptations of novels are the ones that express the heart of the film itself, without being a direct scene-for-scene cut of the story, or you know? Not attempting to be the story at all. The botched Hollywood adaptation isn’t a new concept. Speaking of Frankenstein, it’s well noted that Mary Shelley’s original novel has almost never been directly adapted to the screen and the film version barely resembles the book or its characters (seriously, who is Igor and why is Victor suddenly a doctor?). This may be because Frankenstein so delicately detailed with literary themes. The overtones of responsibility, inner darkness, and atonement are something the narration and writing evoke, and they almost cannot be shown to the audience in a visual sense. What Shelley conveys in Frankenstein would be meaningless on the big screen. There is a similar issue with novels like The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, where both famous versions only resemble their novels by name and concept. Many of the socio-political themes are lost in favor of lighter, less historical fare. Are we right to call Hollywood out for this? Is it fair to a contemporary audience that we include Alice’s Victorian-era political commentary, or Oz’s allusions to 19th century American gold standard debates? These issues were, after all, products of their era. These movies are both very popular, and whether or not we like it, they’re often the first experience people have with these stories. They were the films that introduced me to these novels, in fact, and while I don’t care for them as much as my younger self did, one cannot help but wonder if more movies are capable of this. Can a movie serve as a well-made gateway to the novel without bastardizing the content? (Source: Classic editions of several novels, noted for their widely differences from their movies. Yes, that includes The Wind in The Willows, but we won’t get into Disney for now). I found my answer by way of Neil Gaiman. A lover of experiments and a creative force of nature, Gaiman has done a great deal of screenwriting, but only allowed his original works on the big screen/television handful of times. He reserves the right to be picky, but tries to give each adaption a promise of new experience, rather than being a straight retelling. This is incredibly evident with the 2007 film, Stardust. Searching the reviews for the original novel, it isn’t unusual to encounter readers who grabbed the book because the movie, and who are surprised (or shocked perhaps) at the differences between the versions. Indeed the novel of Stardust reads more like classic a Brothers Grimm folktale, complete with all its brutal violence and sexual themes. There are complex ideas about loss, forgiveness, and growing up. There are hints of English folklore and the old implications of respecting the fae. As a result, several rewrites were done on the movie’s script to help the story along, because many of these ideas and concepts simply did not translate to a screen; Gaiman approved the changes happily. This actually allowed the movie to breathe and expand the universe of Stardust, giving the viewer a fuller, different version of the fairytale without taking away from the original. And funny thing… it works! As it worked in the recent radio show version of Stardust, which is actually read from the perspective of one of the characters, rather than 3rd person. All versions of the story are distinct, and all of them are particularly good. So what is the answer to a strong film adaptation? Do creators need more of a hand in these projects, as with Neil Gaiman, or as Daniel Handler has done with the recent Netflix version of of A Series of Unfortunate Events? Do filmmakers need to be less hasty in churning out new movies for a supposedly impatient audience? Or does a quality of these films lie in something far more complex? There is an art to adapting a story, just as there is an art to telling a story. What works in the format of a film may not work in the format of a novel, or vice versa. While you can never please everyone with the way a story is retold, it makes a great of sense for certain ideas or scenes to change, or end up cut, if they cannot translate into a film. And actually, that’s not a bad thing as long as the new story retains the heart of the original, or at least tries to be of the same quality. From plays in ancient Greece to oral folklore, we do like revisiting our old stories in new mediums, and we still enjoy seeing that today, whether on the screen or stage or Netflix series. There is merit in expecting something memorable and well-written though, and that can mean the difference between outstanding and more Eragons.

0 Comments

|

About MeCaitlin Jones is an author, film editor, and lover of all things Victorian and fantastic. Please check in for information on her upcoming series. Archives

August 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed